It’s All About Being Flexible In 2020: Indian Matchmaking Review

Genre: Netflix Original Series

Available on Netflix

2020 has undoubtedly been the year of experimental relationships for Netflix. From actually wild constraints and novel parameters like these featured in The Circle, Love Is Blind, Dating Around, Too Sizzling to Deal With, and the most recent Love On The Spectrum, the streaming service has offered a preview about love for each viewer’s style.

Marriage has been a popular subject in India, which is very private for the individual, but ironically has always been treated as a social event in which everyone has a say. It can be easily compared to the yearly school gatherings where the trustees and the school principal decide the priorities, date and a budget, the teachers organize the cultural performances, experts are called in to teach the students, and the students perform their talents, while parents come to watch them on the day of the ‘Gathering/Cultural Day’.

Well here on Netflix this year, we have ‘Indian Matchmaking’ – where the parents decide the preferences, wedding budget, and reasons to get married; the expert matchmaker is called in to match the candidates (*and judge them too), and the eligible bachelors/bachelorettes go on dates while the audience watches it as entertainment.

The series has taken up a storm of conversations and arguments and most people are confused about whether they love or hate the series, or they just hate the reality of the Indian Matchmaking scenario it portrays.

Here is my personal take:

- Is it exaggerated?

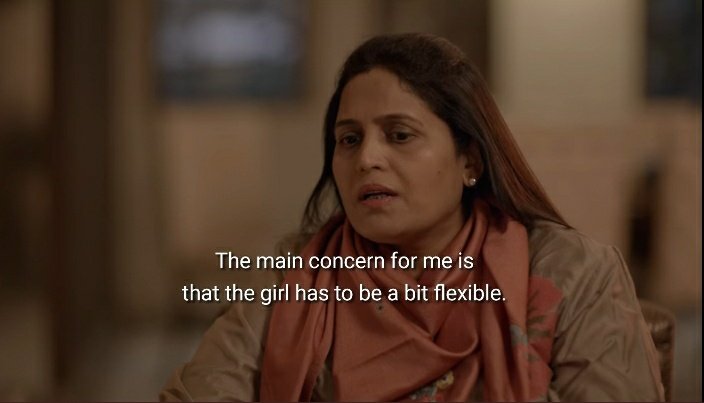

No. And I’ll tell you why. We are in 2020, and so most of us would like to believe that the process has changed, that people are not asked to compromise anymore. That they are not judged by superficial things like skin color, caste, bank balance, height, or education. But the fact of the matter is that this happens all the time! Even in urban places, from the lowest to the highest classes of society. I’ll give you two examples: a friend of mine living in the United States got rejected by the guy her matchmaker had matched her with because he said that she was of his caste, but did not belong to his sub-caste. I guess education and living in a first-world country could not make him grow out of his deep-rooted casteist mindset. Example two: A good friend of mine in India studied for close to ten years to become a high ranking official in the government with a lot of benefits and respect being rightfully deserved by all her hard work. To cater to all the superficial demands, she is also extremely good looking and has a pleasant accommodating personality. And yet, most matches she meets have been rejecting her because they do not want to live and re-accommodate in her government-assigned house with security guards, as that would be non-traditional compared to a woman going to her husband’s house – what we women are often reminded of since our childhood.

So is the show perpetuating stereotypes? Yes, and it is frustrating to watch the whole series. But, at the same time, the generation getting married in 2020 has not completely shed off old beliefs yet. And for most parents trying to get their kids married ‘at the right age’, it’s still a long way to go.

- Does it give a message?

Yes and no. The show is an ugly mirror of how Indian society is still deeply rooted in patriarchy, casteism, and ostensibly defined factors that rule matchmaking. Does this mean every arranged marriage today is forced or follows these regressive set of techniques? No. We see a lot of change and modern approach towards the process taken by singles in India as they look at it as similar to being on dating apps. They take the lead in matching their own candidates through online platforms, being sure of the preferences they have, and meeting people for months on end before deciding to get married. So we see a lot of control shifting from the parents to the singles. It’s no more a ‘chaha pohe’ program done once where the girl and boy just glimpse each other and then meet on their wedding day. However, contrary to popular belief, this scenario is true for a very minor part of Indian society. Most Asian families still actively rule the process of matchmaking for their kids and decide all the ‘who, what, when, and where’. So the show depicts this through the candidates and their parents showing not much has changed when it comes to traditional values governing the process – for example, we see a divorced Punjabi single mom considering a match given by Sima whom she likes based on his biodata, but her father puts his foot down by saying that this man will not be a good match as he is divorced from his wife who is a white woman.

- Was Sima Taparia a necessary element?

I saw Sima Taparia, the celebrated matchmaker first in the documentary film – ‘A Suitable Girl’ in which her daughter was one of the three girls whose journey to selecting and getting married was followed by directors Sarita Khurana and Smriti Mundhra. And while that is a brilliant documentary to watch, the show here lets Sima take a lead in setting the mood for the arrested development of the social psyche in the upper-middle class of Indians both in the home country and abroad. Her snap judgments which she calls ‘observing’ and ‘knowing how to read’ people, set the stage for some cringe-worthy moments for people who have evolved past it all. (If you do not feel the cringe, then honestly you have some inward thinking to do). Sima here, I feel, symbolizes the upper-middle class itself which matches everything from the status quo to skin color, to caste and education. Everything except love. Because who needs love when you are choosing a stunning daughter-in-law with good education to parade among your social circle? Love is secondary. And Sima knows this well. She caters to the parents first, the singles second and to logic – never. And if she can’t find a ‘successful match’, she is clever enough to not take the blame!

- What more could have been done on the show?

At the beginning of every episode, the show portrays an old experienced couple who reiterates the philosophy that arranged marriages work and are successful most of the time. In India, with taboos against separation, divorce, or even widows, it’s hard to determine the factors that contribute to a long marriage. But lets for a minute consider all marriages are happy and successful here – there could have been elements like cases of breaking stereotypes in matchmaking. Or people with parents that have moved beyond the conventions of wanting the fair, flexible, and submissive match and are supportive of the candidates to make their own choices. Or people of different ages trying to find a match (except the 20-35 age group), or same-sex couples. Also, giving some legal information about the rights and responsibilities while entering into a marriage would have been tremendously helpful for people to know the dos and don’ts dictated by marriage laws in India. I think this concept has many more opportunities to break stereotypes and taboos for people in today’s generation and give cultural education for these changing times to people being part of these stereotypes. The show definitely has missed some opportunities to do that.

Similar to this:

Books – The Marriage Clock, The Matchmaker’s list

Films – A Suitable Girl, Love Is Blind

Overall the show did what it wanted to do – show how things work in this sphere on a majority level. It reveals many blemishes in the way that Indians look at love and marriage. Oscar-nominated director Smriti Mundhra, an executive producer for this show, said she has purposefully not edited out these uncomfortable moments. Her decisions are intentional and calculated and intended to effect change. In response to the mixed reviews, Smirti stated that she hoped that “it will spark a lot of conversations that all of us need to be having in the South Asian community with our families — that it’ll be a jumping-off point for reflections about the things that we prioritize, and the things that we internalize.” Smriti is not redeeming the cavalier manner in which families perpetuate inequality and outdated thinking. She’s exposing it.

The mirror is being held up and it’s impossible to look away.

The frustration at large is towards the mindset of people in this show, and especially the matchmaker Sima Taparia. As every dating show goes, (like The Bachelor), none of Sima’s candidates got married.

Unilever may have announced last month that it is removing the word “fair” from its Fair & Lovely line of skin-whitening products. But it will take a lot more to change the hearts and minds of people in our society to make the literal change. Singles in the show like Vyasar, Nadia and Ankita have paved the path of finding their true mate through understanding, openness and love, and I hope this new outlook towards matchmaking gets appreciated and adopted by more singles in India.

Here’s hoping Season II of Indian Matchmaking shows us exactly that!